Each charger: 12 ½ in (31.5 cm) diameter

cf. Japonisme: From Falize to Faberge, The Goldsmith and Japan, exh. cat., Wartski, London, 10th-20th May 2011, p. 36, no. 51 – for a charger of similar form and design

Haydn Williams, Enamels of the World 1700-2000, 2009, p.252-253, no.172 – for an illustration of a charger of similar form in the Khalili Collection

Victor Champier, 'Les Artistes Decorateurs – Fernand Thesmar', Revue des Arts Decoratifs, 1896, pp.373-381

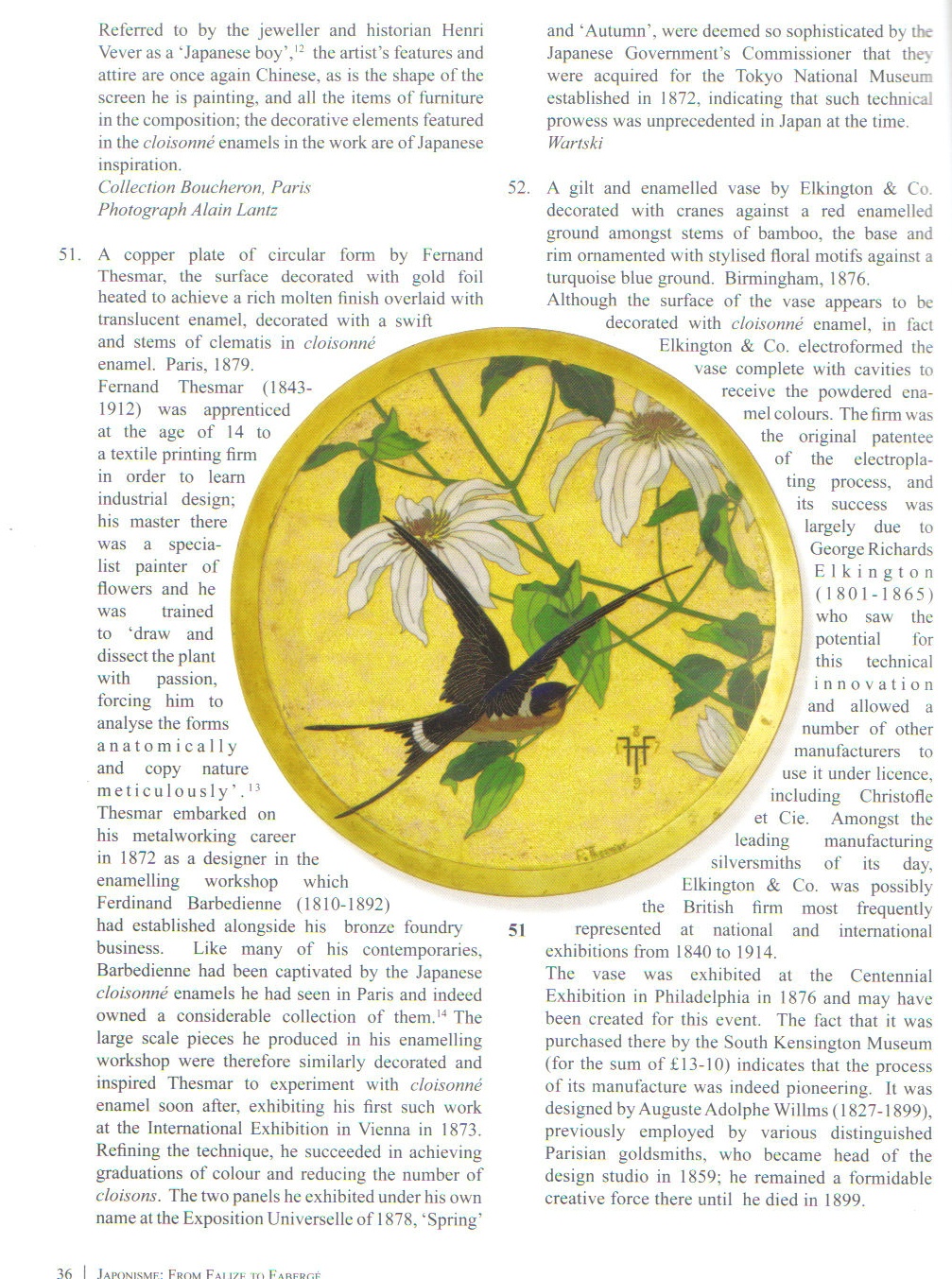

Fernand Thesmar (1843-1912) was born in Chalon-sur-Saône in 1843. Chemistry held an early fascination for him, but he was trained as a designer of textiles in Mulhouse and learnt to dissect and draw plants starting at the age of 14. In 1860 he left for Paris where he continued to work in textiles. In 1872 he was invited to devote himself to cloisonné enamels by Ferdinand Barbedienne who had already formed an outstanding collection of Japanese enamels. Like many of his contemporaries, Barbedienne had been captivated by the Japanese cloisonné enamels he had seen in Paris and owned a considerable collection of them. The large-scale pieces he produced in his enamelling workshop were therefore similarly decorated and inspired Thesmar to experiment with cloisonné enamel soon after. He exhibited his first work at the International Exhibition in Vienna in 1873.

During the 1870s, Thesmar’s cloisonné enamels won an international reputation. While Lucien Falize found some grounds for criticizing Thesmar’s use of half-tones and of large cloisons in the enamels shown at the Paris Exhibition of 1878, he did not question his virtuosity. The two panels Thesmar exhibited at the Paris Exposition in 1878, Spring and Autumn, were deemed so sophisticated by the Japanese Government’s Commissioner that they were acquired for the Tokyo National Museum established in 1872, indicating that such technical skill was unprecedented in Japan at the time.

Despite his success, Thesmar’s finances were precarious. In 1888 he found himself excluded from his workshop by his landlord. To his aid came first a firm of art dealers, and then the redoubtable Alfred Morrison, the great collector of manuscripts and the patron of Plácido Zuloaga. In the year of his troubles, Thesmar perfected the technique of plique-à-jour enamelling, in which translucent enamel is held in its cell without backing. Morrison bought an early example, tracked Thesmar down to his workshop in Neuilly-sur-Seine, and invited him to London. He appears to have remained there until about 1890 when the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris purchased two small plique-à-jour bowls.

In 1912, the year of his death, Thesmar was described by Henri Bouilhet as not only in the front rank of enamellers, but the best. Similar chargers by Thesmar are held in the collections at the Musée d’Orsay and The Cleveland Museum of Art.